Echoes from Adelaide’s past

Layers of development may have covered up some of Adelaide’s history, but there are still a few remnants and reminders that have stood the test of time.

We’ve uncovered four sites around metropolitan Adelaide that tell fascinating tales from our state’s history.

The forgotten railway platform

(Plympton – cnr of Marion Rd and Mooringe Ave)

The City to Bay tram service was once a suburban railway operated by the Adelaide, Glenelg and Suburban Railway Company. In 1880, a competitor, the Holdfast Bay Railway Company, opened a second service following a route that has since become the Westside Bikeway. Not much is left of it now, except the old Plympton Railway Station platform on Marion Rd, opposite Mooringe Ave.

The two companies eventually merged and were later taken over by the State Government. Both services continued to run until the Holdfast service closed in 1929, at which point the City to Bay line converted to trams.

Side note

Another line, running beside the dunes between Glenelg and Marino, was opened in 1879 but poor patronage, sand drifts and a couple of fatal accidents saw it close about a year later.

The road to nowhere

(South Park Lands/Tuthangga (Park 17))

Elm Carriageway is a 21m-wide tree-lined avenue running between Hutt Rd and Beaumont Rd in the South Park Lands. Developed in the late 1800s, it was the brainchild of Scottish-born sylviculturist, John Ednie Brown, who was South Australia’s first Conservator of Forests.

Responsible for treeing much of the Park Lands, he felt that “fine shady walks should form a marked feature in the landscape”.

There’s no longer a walking trail or carriageway between the trees, but the parallel rows of English elms provide an insight into the early settlers’ desire to recreate the old country.

By the time he’d reached SA, Brown had already received accolades for his work in the UK and USA. His fame grew, and in 1890 he was poached by the NSW Government, where he became director-general of forests, before moving to WA where he spent the rest of his life.

Side note

In 2017, the little-known John E Brown Park (aka Park 27A) was dedicated in his honour. Nestled between Bonython Park and the Outer Harbor train line, it’s the site of The Deceased Workers Memorial Forest and The Bunyip Trail – an activity trail for kids.

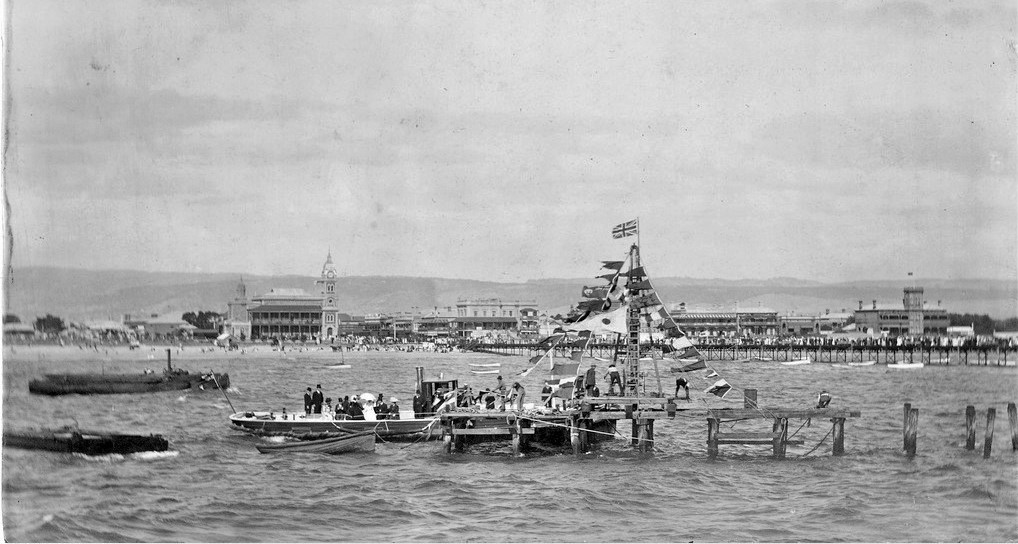

The broken breakwater

(off Glenelg Jetty)

In the early 20th century, a breakwater was very nearly built just off the Glenelg Jetty. The first attempt in 1908 involved pile-driving an arc of concrete pylons into the seabed, but the project was beset with problems from the start. Workers with marine pile-driving experience were hard to come by, and the offshore rig was a dangerous workplace in high seas.

Several foremen resigned due to the difficult conditions, and the ceremony to drive in the first pylon was a near disaster. The Australian Governor-General was set to officiate, but the inaugural concrete pylon broke free from the crane in choppy seas and sank, delaying the event. A wooden replacement was rushed to the scene to complete the ceremony. Amid fears for his safety in the rough weather, the Governor-General was hurried to and from the rig. The windy weather ensured there were no speeches.

Work continued but there were more – mostly weather-related – mishaps. Then, when several of the installed columns cracked during a storm, the whole project was stopped and never restarted.

In 1914, the Stone & Siddeley Company tried a different method using caissons (waterproof cement boxes filled with sand and sealed) as foundations, but a couple of storms destroyed their work and the job was never finished.

Visible from the end of the jetty at low tide (see the main photo at the top of the page), the remains of the Stone & Siddeley effort make a good dive site, cormorant perch and occasional seal hangout.

Side note

A consulting engineer for the first project was John Monash, later General John Monash, who went on to command all of Australia’s troops in Europe during WWI before having a Riverland town and Melbourne university named in his honour.

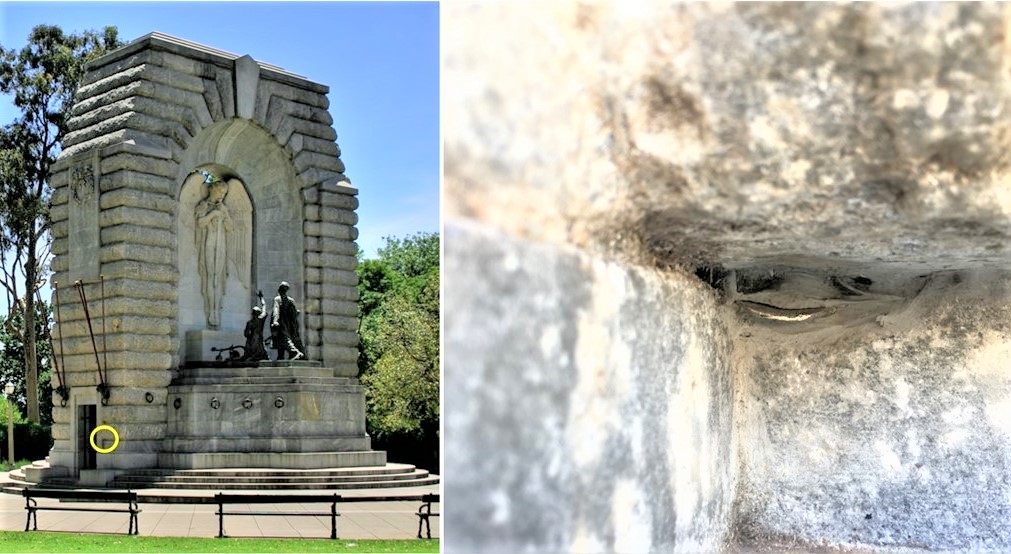

A florin frozen in time

(National War Memorial, North Tce)

Hidden beneath a ledge near the southern entrance of the National War Memorial, there’s a florin (2-shilling coin) cemented into the wall. Over the years, there’s been considerable speculation about its origins and purpose, but an article from a 1949 edition of The News seems to clear up the mystery.

“When the work on the memorial began more than 20 years ago [city architect] Mr [Harold] Griggs was the construction engineer. It’s an old custom to put a coin in the base of a new building: Mr Griggs thought one should be put in the war memorial. He gave a florin to the foreman, who put it in the concrete. As simple as that.”

Side note

The article goes on to say, “During the depression, when two shillings was almost half the weekly dole, many people tried to get the coin out. No one succeeded. The concrete holds on to it like a miser.”

Experience more of South Australia

Looking for something to do? Check out some of the great experiences our state has to offer.