Disaster at sea: 3 South Australian shipwrecks

In the early days of maritime expeditions, high seas, shallow reefs and incomplete navigation charts made sailing through SA’s waters a hazardous occupation.

Many ships survived lengthy journeys from England and elsewhere, only to be smashed to pieces on South Australian shores. There are more than 800 recorded shipwrecks along the state’s coast. Here are the stories of just three of them.

SS Clan Ranald

On 31 January 1909, the 108m-long SS Clan Ranald was steaming past the bottom of Yorke Peninsula in rough seas on its journey from Port Adelaide to South Africa. Laden with wheat, flour and coal, the ship suddenly tilted 45 degrees, before capsizing 700m offshore from Troubridge Hill at about 10pm. Distress rockets were fired but they were ignored by the nearby SS Uganda.

Locals saw the rockets and rushed down to the beach to help survivors make it to shore. Tragically, 40 of the 64-man crew lost their lives.

The cause of one of SA’s worst maritime disasters was never confirmed, but it’s possible a load of coal on the deck shifted in the rough seas.”

At the time, there was a lot of finger-pointing over who was responsible.

The European officers who died, including the captain, were buried in the main section of Edithburgh Cemetery. The mostly Filipino and Indian crew, known as Lascars, were interred in a large communal grave in the cemetery’s back corner, marked with a plaque reading, “31 Asiatic seamen, names unknown”. In 2009 a new plaque was installed which included the sailors’ names.

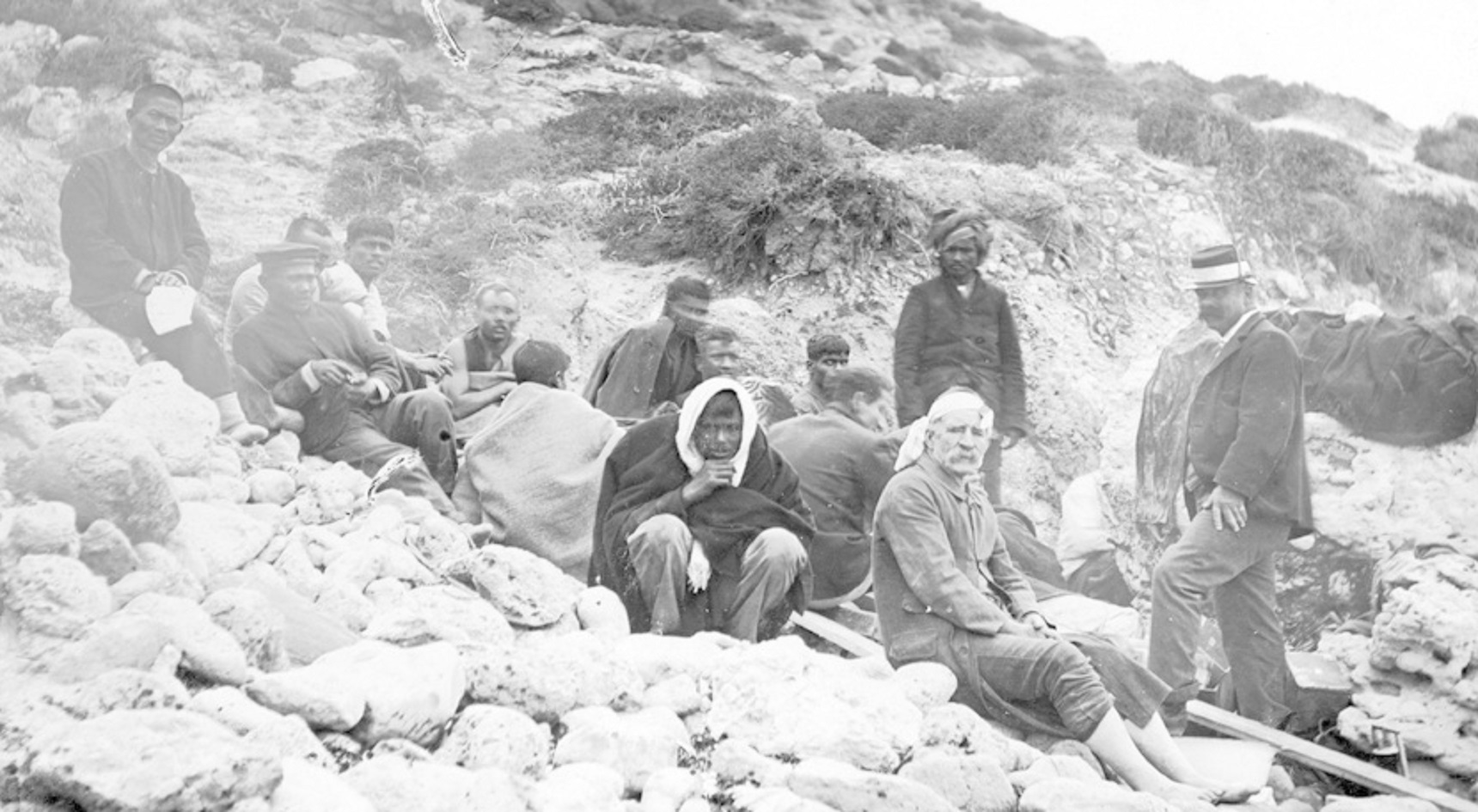

The surviving Lascars were cared for by locals, and later by people in Adelaide. But in line with the White Australia Policy of the day, they were eventually deported as illegal immigrants. This caused such an outcry that the Federal Government changed the rules to allow shipwrecked Lascars to remain in Australia.

The wreck was found in 1962 and the anchor was recovered in the mid-1970s. It was displayed atop the cliffs near Troubridge Hill Lighthouse, but over time corrosion took its toll and it was eventually removed for restoration. It now sits on the median strip in front of Edithburgh Museum, which houses artefacts from the wreck.

The SS Clan Ranald lies beneath 20m of water and is only suitable for experienced scuba divers as strong currents can make it a challenging dive.

Star of Greece

Built in Belfast in 1868, the Star of Greece was a 69m-long, three-masted iron sailing ship. Under the command of 29-year-old Captain H.R. Harrower, the ship left London for Adelaide in March 1888, carrying a 20-tonne gun destined for a proposed fort at Glenelg. As well as Fort Glanville and Fort Largs, there were plans for a third fort at Glenelg – all three to be connected by Military Road – but it was never built. Adelaide’s coastal forts were constructed due to fear of a Russian invasion.

The Star of Greece made it to South Australia safely and, after loading up with wheat, departed Adelaide at 6.30pm on 12 July 1888 for the return trip to England. In the early hours of the following morning, she was hit by a powerful gale and was pushed off course. The ship ran aground about 200m offshore from Port Willunga at about 3am and quickly began breaking up.

The crew were unable to launch the lifeboats and the distress rockets were too wet to fire. The alarm wasn’t raised until a boy walking along the beach saw the foundering ship at about 7am.

The nearest telegraph office at Willunga didn’t open until 9am, so it wasn’t until 9.30am that authorities in Adelaide had any idea there was trouble down south.

Rescue ships were eventually despatched from Port Adelaide and rescue equipment was sent from Normanville. By the time the much-delayed help arrived, the ship had sunk. Despite Star of Greece being in shallow water only a short distance from the shore, 18 sailors died in the mountainous seas and only 11 made it to the beach.

The locals did everything they could to help the sailors reach the shore, with police Constable MC Tuohy winning an award for bravery.

An inquiry into the delayed rescue effort recommended rescue services be more responsive and better equipped, and that telegraph stations be available 24/7 in an emergency.

The ship’s figurehead and other relics from the wreck are on display at the South Australian Maritime Museum at Port Adelaide.

There’s a monument and mass grave for 11 of the drowned sailors, including the captain, at the Aldinga Uniting Church Cemetery.

On a calm day, the sunken ship is an ideal spot for snorkelling, with plenty of fish, soft corals and other marine life.

Zanoni

Among maritime historians, the Zanoni shipwreck is considered a rare find. It’s the only composite (iron frame, clad with timber planks) barque – sailing vessel with three or more masts – in reasonable condition to be found in SA waters.

Built in Liverpool in 1865, the Zanoni was a 44m-long, 307-tonne, three-masted sailing ship. Departing for her maiden voyage in February 1866, she sailed to Peru and Mauritius, before arriving in Port Adelaide with a load of sugar almost a year later.

After picking up wheat and wattle bark (used for tanning hides), she headed to Port Wakefield to load more wheat.

Returning to Port Adelaide for clearance to London, the ship was hit by a freak storm in Gulf St Vincent in the early afternoon and capsized. It sank in minutes, but fortunately the crew were able to make it to a lifeboat that had broken free from the wreck.

The storm died down as suddenly as it had arrived, and at around 11pm, all sixteen men were rescued by the sailing ketch Powles.

Although the crew had a fair idea where the ship went down, the wreck wasn’t located until 1983, 166 years after it sank. The discovery came when abalone diver John McGovern offered a reward for information about its location. Retired fishermen Rex Tyrell took Mr McGovern and diver Ian O’Donnell to a site 15km offshore from Ardrossan. The men found the Zanoni 18m beneath the sea.

The wreck has been declared a Historic Shipwreck under the Historic Shipwreck Act 1981 and a permit is required to come within 500m of the site and dive on it.

An extensive collection of artefacts from the Zanoni, including the ship’s bell, can be found at the Ardrossan Heritage Museum.